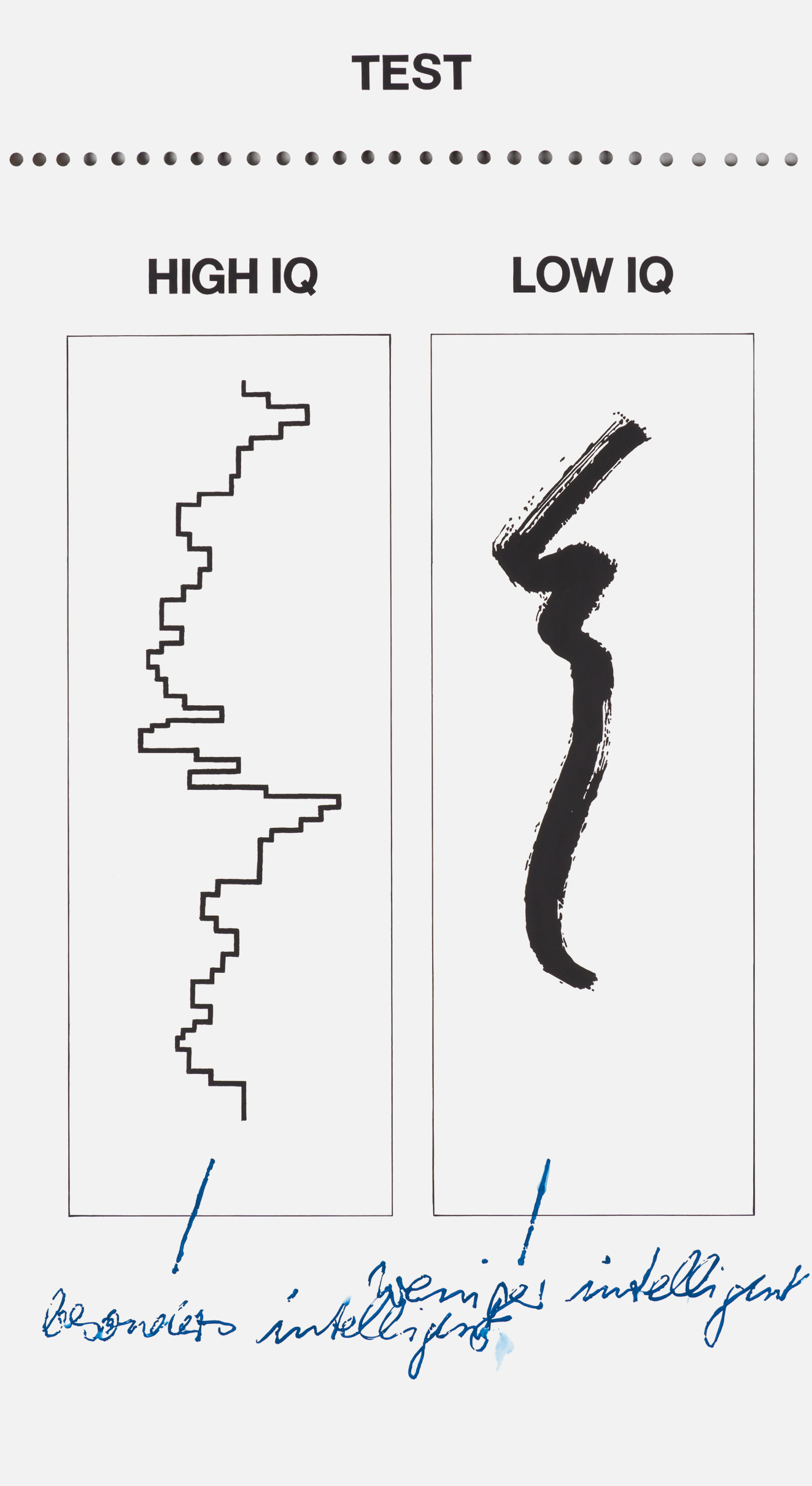

KP Brehmer, Test (Hot-Cool Painting), 1973/74, acrylic on plastic, 220 x 120 cm, © KP Brehmer Estate, Berlin

Oskar Weiss is pleased to announce KP Brehmer Rendering Exhaustion: Works from the 1980s, curated by Elisa R. Linn and Lennart Wolff, the next exhibition in his gallery. Focusing on the later phase of Brehmer’s work, the exhibition includes twenty paintings and works on paper from the artist’s estate, many of which are exhibited here for the first time.

“Extension of representational properties in painting. First heat paintings since 1973. As a new dimension, heat is included in the painting. All bodies radiate heat in the form of invisible infrared radiation. It can be caught with infrared devices and converted into visible images. This is done using high-sensitivity detectors, which convert the thermal radiation into electrical signals, which are then amplified and displayed on a screen. These images are the ‘model’ for my paintings. Thermal images look alienated compared to conventional photographs. Warm persons and objects appear bright, less warm ones dark.”

– KP Brehmer

In 1979, riding the wave of electoral triumph, Margaret Thatcher declared, “Conservatives must rekindle the spirit which the socialist years have all but exhausted,” calling for nothing less than a radical shift in how we see the world — a wholly “new attitude of mind.”¹

The exhibition Rendering Exhaustion traces KP Brehmer’s (1938–1997) artistic output during a period of profound social, political, and economic shifts in the West: the exhaustion of the Keynesian Consensus and its welfare state, deindustrialization, declining unionism, and the rise of finance. As individualism became the dominant cultural and political frame work, the artist — trained as a photomechanical reproduction technician — turned increasingly to figurative and gestural painting and watercolors on canvas, depicting cropped body parts in vivid colors and portrait-format heads, many of whom bear titles that convey fatigue, such as Müder Kopf (Kopf I) and Schlafender Kopf (Kopf II) (both 1985).

This exhibition, one of the first dedicated to Brehmer’s 1980s work, focuses on his Wärmebilder [Thermal Images], paintings derived from thermographic images in scientific and medical studies. Rendering Exhaustion employs the metaphor of depletion in two senses: the exhaustion of economic, political, and ideological systems, and the deliberate overworking of images through reproduction, manipulation, and serial variation, as seen in works like Kuss 1–3 (1982). While these works differ markedly from his earlier appropriations of maps, state symbols, and statistics, they should not be seen as a rupture. Instead, they reflect a careful recalibration of his artistic tools in response to the evolving dynamics of power, capital, and the information and image economies.

Deeply engaged with social issues, Brehmer saw his work as part of an ongoing, processual dialogue with society, stating that “I am not interested in ‘reproduction,’ but rather I am trying to force my production materials into parallel processes.” In a decade marked by the proliferation of early digital imagery, novel satellite and medical imaging, and increasingly sophisticated cameras — technologies that mediated new ways of seeing a rapidly changing world — this approach led him beyond the appropriation and re-rendering of diagrams and statistics of welfare-state biopolitics. He also moved past overtly political or propagandistic visual material from the Cold War, whose rigid, oppositional logics were beginning to thaw.

Attuned to the coding of color, Brehmer explored how heat cameras translated bodily “thermal radiation into electrical signals, amplified and displayed on a screen,” (KP Brehmer) automatically rendering it in false colors. Technical breakthroughs in these cameras, initially developed for military and scientific purposes during the 1970s, opened new possibilities for visualizing the body. While a new generation of German painters — the so-called Junge Wilde — revived expressive, figurative painting in the early 1980s, any superficial resemblance to their work is misleading: Brehmer’s figures were not derived from life, memory, or conventional photographs, but from technical images that had already undergone multiple layers of coding and translation. In this sense, the paintings are conceptual from the start, reflecting what Vilém Flusser describes as the nature of technical images, which—unlike traditional ones—convey underlying ideas rather than simply representing phenomena. One of the earliest paintings in the exhibition, from 1974, makes this revelation explicit: a composition of abstract colored shapes is paired with painted text reading, “This is not a modern painting, but a ‘heat photograph.” This is also the case with later works such as Schlafen (Du oben, ich unten), Rot = Traum, (1984), a seemingly abstract Color Field painting that, only through its title, reveals its basis in a study of sleep qualities — a quasi-portrait of the artist and his partner, still dreaming in red, the color of socialism. The couple here mirrors the binary logic of code — 0 and 1, “you above, I below” — while also recalling Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s “plus and minus,” where warm/light and cold/dark colors form a dialectical interplay of qualities and emotions. At a moment when research into sleep and its disorders was advancing, Brehmer’s appropriation can be read beyond the scientific and medical context — as a reflection on the rise in tracking and metricization of the innermost personal — anticipating what Shoshana Zuboff later termed surveillance capitalism, enabled by a “habitat” of neoliberal ideology and policy.²

From early works such as Test (Hot-Cool-Painting) (1973/74) — a mixed-media canvas resembling an enlarged IQ test — to later pieces like Deutscher Mann III (Ausschnitt) (1995), painted from a diagnostic thermographic image of a headache with the brain rendered in the colors of the German flag, proportioned to the distribution of wealth, Brehmer’s practice operates diagrammatically, as Doreen Mende notes. His works do so not merely by appropriating motifs from scientific studies, but by constructing layered, multi-vector discursive spaces deliberately punctuated by voids where political and social subjects might emerge.³ Brehmer coined this practice Sichtagitation, the “agitation of sight,” akin to what Flusser described as decoding. At the time, Flusser published his seminal Into the Universe of Technical Images (1985), defining decoding as the active unravelling of apparatus-generated images, revealing their mediations and underlying structures.⁴ In line with this, Brehmer’s Wärmebilder thermographic works compel viewers to read against the grain, provoking critical engagement rather than passive consumption — a practice he described as “sharpening their senses,” and one that anticipates what is now called critical data literacy: the capacity to question and make sense of the hidden infrastructures that ceaselessly gather, shape, and circulate the data structuring the everyday.⁵

Whether in his iconic earlier works or his later thermal-image paintings, presented here, Brehmer’s practice consistently operated across three interwoven axes: the political economies and broader social transformations around him; the evolution and mediation of technical image-making; and the shifting histories and aesthetics of art itself. Ultimately, the works gathered in the exhibition re-paint a historical moment in which the exhaustion of the postwar order not only fostered countercultures and artistic innovation but also fueled a surge of right-wing politics. These forces positioned themselves as “new” alternatives, promoting economic “liberation” while simultaneously advancing nationalist and heteronormative restorations. With communist states as Cold War adversaries in decline, new “enemies” were cast in their place: movements for environmental protection, feminism, anti-racism, and queer rights, all opposed by the right, which framed them as absorbed into the state and against which a new populism had to be mobilized.⁶ In this context, the ideology of an “ethno-economy” — a fusion of neoliberal rationalities and ethnonationalist and authoritarian tendencies which dress racist concepts in the ostensibly neutral language of science via biometrics, performance data, and IQ tests — has gained increasing traction. It is particularly embraced by what McKenzie Wark calls the “vectoralist class,” a ruling elite that controls the networks and platforms through which information flows and is commodified. Brehmer’s work — attentive to the visual languages and legacies of authoritarianism and fascism, as well as to the bodily and social codifications of an ever-transforming capitalism — renders visible how these intersecting political, economic, and cultural shifts shaped both individual and collective experience, ultimately aiding us to decode the images and ideas through which the right continues to construct its “new attitude of mind” today.

¹ Margaret Thatcher, “Speech to Conservative Party Conference,” October 12, 1979, Margaret Thatcher Foundation, https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/104147.

² Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (PublicAffairs, 2019).

³ Doreen Mende, “Aus einer diagrammatischen Praxis: KP Brehmer,” in NO PROOF OF EVIDENCE. Kritische Aneignungen grafischer Visualisierungsstrategien in der Kunst. Documentation of the Symposium at the Berlinische Galerie, June 7, 2013: (Berlinische Galerie, Landesmuseum, 2013), 25.

⁴ Vilém Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images (University of Minnesota Press, 2011), originally published 1985.

– Elisa R. Linn and Lennart Wolff